Influenza and sudden death in healthy children: results of a surveillance survey

The announcement by WHO, in June 2009, of the first pandemic of the 21st century gave way to the exceptional measures envisaged by the pandemic plans of the single countries and aroused anxieties and fears with their roots in the tragic events of the past. As the months went by, the impact of the pandemic appeared modest and the initial scepticism turned to fierce criticism of the world's top health authority, who were accused of having acted solely to favour large pharmaceutical companies. Many authoritative voices in the scientific community raised doubts and the issue ended up under the lens of the Council of Europe. The official death toll of 18,000 victims worldwide1 was deemed a categorical condemnation of an unjustified alarm and an event that, according to certain rumours, would prove to be less severe than traditional epidemics.

In fact, the error made by many commentators was to ignore the lessons of the previous pandemics and the most recent literature data, which throw a completely different light on events. Only the officially-recognised deaths were considered a true reflection of the severity of the epidemic, when in reality it should be known that the effect of events of this magnitude can be calculated either on the basis of mortality tables, through ad hoc studies performed a posteriori2, or through the use of rapid mortality indicators, such as those available to the United States 3 and other European countries of the EuroMOMO 4 circuit, but not to Italy.

Thanks to these studies, in the USA it was possible to calculate a real death toll at least 5-6 times higher than the official figures5, and between 200,000 to 400,000 deaths worldwide6. Significantly, 80% of these involved subjects under the age of 65, many aged between 30 and 50 years of age. Moreover, preliminary data from both experimental and clinical scientific studies had highlighted the danger of the virus, which was capable of causing devastating signs of multi-organ failure in young subjects and sometimes perfectly healthy individuals, but they were not taken into consideration 7.

In recent history, a similar situation occurred with the pandemic of 1968-69. There is no trace of this particularly dramatic event in the collective memory of our country, yet analysis of the mortality tables reveals a heavy toll, with more than 57,000 deaths including a significant number in childhood deaths8.

The fact is that many deaths escape surveillance because they are masked by respiratory, cardio-circulatory, neurological and infectious diseases that do not directly reveal the true underlying cause. It should be noted that the most fatal season of the 1968 pandemic, at least in Europe, was not the onset of the H3N2 virus, but the subsequent one.

During 2009, we saw above all macroscopic communication errors by the Italian health authorities that, on the one hand, pushed for a vaccination campaign that should have involved millions of people but at the same time minimised the scope of the event, ending up disorienting a population already confused by contradictory messages. From this came the sharp fall in trust in our institutions and the complete failure of the ambitious vaccination programme.

The 2010-11 season, marked by the return of the H1N1 virus, was announced as a sign of a return to "normality", as if to make up for earlier mistakes. The pandemic lesson of 1968 should have encouraged greater prudence and instead it was decided not to adopt even the limited surveillance measures that had been used during the first pandemic season.

Given the absence of official bulletins, it is only thanks to the scant news reported by the local press that it was possible to learn of various cases of people subjected to ECMO and a not inconsiderable number of deaths, which health officials were quick to attribute to the vulnerability of the people involved. In the same periods, England 9 and Greece 10, unknown to us, witnessed a dramatic season, with the health systems of those countries in serious difficulty and with a final death toll of several hundred, mainly among the younger age groups.

During my online research, I began to find a seemingly abnormal number of sudden deaths in children and young adults who died suddenly or a short time after the onset of presentations of infection, however slight. By the end of the season, I had documented approximately 90 subjects under the age of 35, who had no apparent previous health problems and who died in circumstances that can be defined as mysterious. A possible connection could have been made with similar cases described in the course of previous pandemics, such as in 195711, but at the time I had no other element that could support my suspicions. The turning point came in May 2011, when I happened to read a news article about a 16-month-old English infant found dead in her cot. Her mother had checked on her a few hours beforehand and noticed nothing out of the ordinary. The autopsy showed pneumonia and, after a series of in-depth examinations, the responsibility of the pandemic virus was ascertained. Subsequently, other cases were reported in England and other parts of the world. In November of the same year an article by Japanese authors was published, reporting a number of children who had died suddenly: in all 40 fatal cases, of which 13 perfectly healthy children died as a result of cardio-respiratory collapse which occurred outside hospital and 34 died within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms12.

This article prompted me to look for similar descriptions in the international literature. In the first year of the pandemic, in the USA, 67 children out of 270 died as a result of cardiac arrest before admission to hospital13. In England 16 out of 70 children, in whom a significant absence of risk factors was reported, were in cardio-respiratory arrest upon arrival at the emergency room14. Deaths of this nature are not exclusive to the pandemic virus. Sporadic cases are described in the literature in connection with seasonal viruses (often type B) or more aggressive variants. In the United States at the end of the 2003-04 season, there was a toll of 153 fatal cases, 1/3 of which with the characteristics of sudden death15. In the same period, in England, the deaths of 17 children were reported, of which 4 were fulminant and 4 in the absence of symptoms or within 6 hours of their onset16.

Prompted by this data, I decided to repeat the monitoring of sudden and fulminant deaths during the following season. The 2011/12 season was characterised by a slightly milder trend in the number of ILIs and by an almost absolute prevalence of the seasonal H3N2 virus. This allowed me to compare the two seasons taking into account their different epidemiological profiles. From the data collected, I extrapolated those referring to the paediatric population aged between 3 months and 18 years, which became the subject of a study published in the journal JPHRES in July 201217.

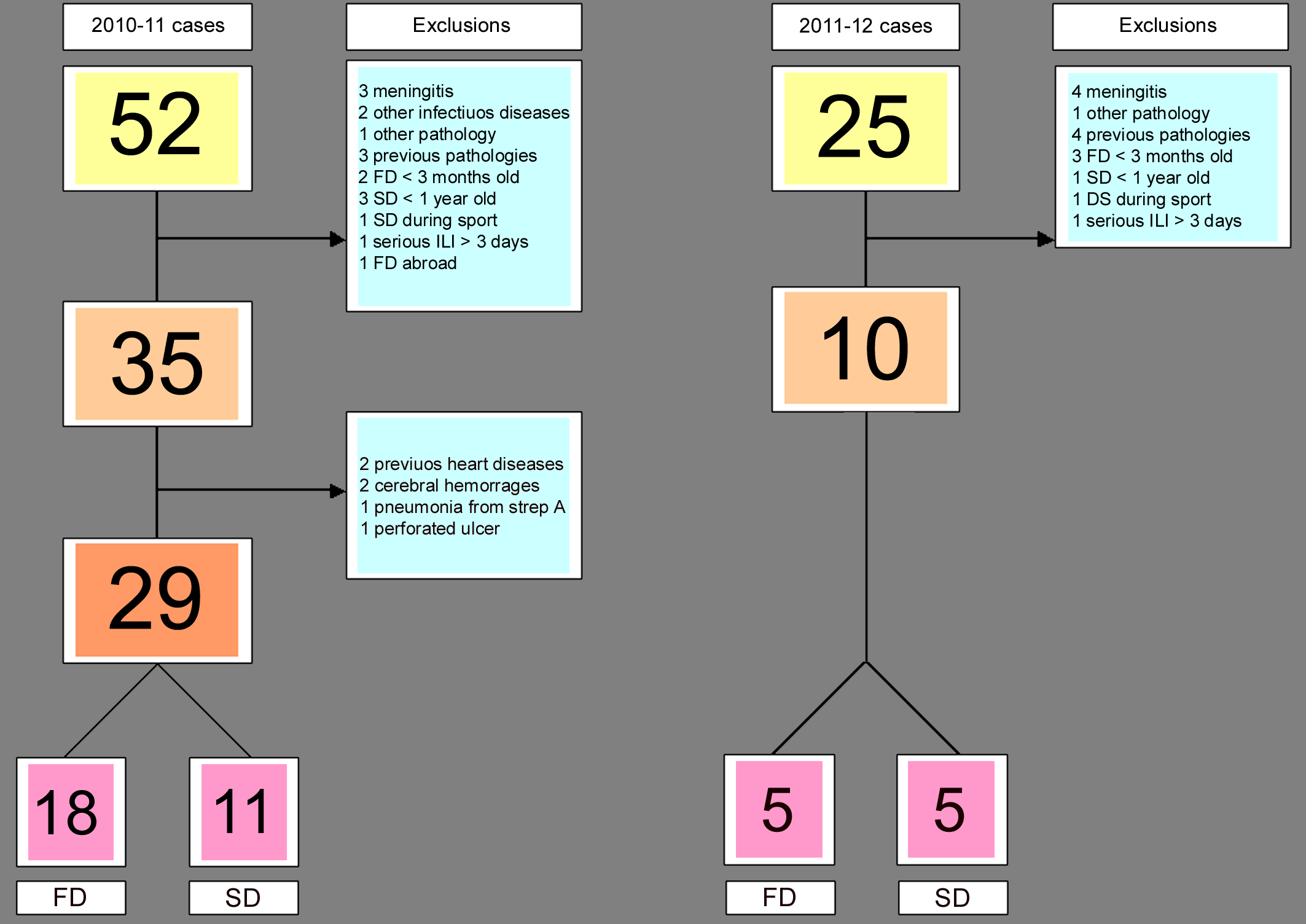

With a systematic search of the news reported by the Google search engine, I documented 29 deaths in the 2010/11 season, 18 fulminant and 11 sudden. During the 2011/12 season there were 10 cases, 5 of fulminant death and 5 sudden.

Search algorithm. FD = fulminant deaths, SD = sudden deaths.

Most events occurred during the period of peak circulation of the influenza virus. The fulminant deaths were therefore 3 times more frequent during the first season and involved children of a higher average age than the following season. It is obviously impossible to give a definite explanation for the difference in the number of fatal events found, but one legitimate suspicion is that at the base of this substantial increase may have been the H1N1 virus, in its second season in Italy and no longer at the centre of attention as in 2009.

In Italy the awareness that influenza can cause death in healthy subjects is lacking. It tends to be considered as a serious disease only for weak and frail subjects, which means it is rarely suspected or tested for in seemingly healthy individuals. In England and the USA, there have been more than ten years of operational investigative protocols which, thanks to the use of the most advanced diagnostic technology such as molecular technology, allows us to shed light on many of these cases. An article recently published in the journal Pediatrics highlights, for the first time, how 1/3 of the flu deaths in the United States between 2004 and 2012 were of this type, i.e. with a significant absence of risk factors18. This is not just a matter of acquiring a knowledge that broadens the spectrum of flu-related illnesses and which every doctor should be familiar with; there is also the issue of helping families whose children have been taken away so dramatically to at least gain some closure and avoid recourse to legal action, although their grief may never be eliminated. Unfortunately in recent years, several legal cases have been reported in the media involving esteemed colleagues who have been accused of and, in some cases, even condemned for the fulminant deaths of unidentified causes in children.

It is to be hoped that also in Italy the data from international literature and the indications arising from my study may prompt a debate and research into the sudden and fulminant deaths of healthy children linked to influenza.

Equally important is the adoption of the most advanced epidemiological investigation tools in order to be better equipped to deal with future emergencies that may be much more severe than the last pandemic.

Sources / Bibliography

- Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 — update 99. Geneva: World Health Organization, May 7, 2010. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2010_05_07/en/

- Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Williamson GD, Stroup DF, Arden NH, Schonberger LB. The impact of influenza epidemics on mortality: introducing a severity index Am J Public Health. 1997 Dec;87(12):1944-50

- Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Stroup DF, Williamson GD, Arden NC, Cox NJ. A method for timely assessment of influenza-associated mortality in the United States. Epidemiol. 1997;8:390-395

- Nicol A, Ciancio BC, Lopez Chavarrias V et al Influenza-related deaths - available methods for estimating numbers and detecting patterns for seasonal and pandemic influenza in Europe. Eurosurveillance, Volume 17, Issue 18, 03 May 2012

- Updated CDC Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Influenza Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths in the United States, April 2009 – April 10, 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/estimates_2009_h1n1.htm

- Simonsen L, Spreeuwenberg P, Lustig R, et al. Global mortality estimates for the 2009 influenza pandemic from the GLaMOR project: a modeling study. Plos Med 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001558

- Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza. Clinical Aspects of Pandemic 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infection N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1708-1719

- Rizzo C., Bella A., Viboud C., Simonsen L., Miller M. A., Rota M. C., Salmaso S., Ciofi degli Atti M. L. "Trends for Influenza-related Deaths during Pandemic and Epidemic Season, Italy, 1969-2001". Emerging Infectious Diseases Vol 13, N. 5, May 2007

- O. T. Mytton, P.D. Rutter and L. J. Donaldson. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in England, 2009 to 2011: a greater burden of severe illness in the year after the pandemic than in the pandemic year. Eurosurveillance, Volume 17, Issue 14, 05 April 2012

- Athanasiou M, Baka A, Andreopoulu A, Spala G, Karageorgou K, Kostopoulos L, et al. Influenza surveillance during the post-pandemic influenza 2010/2011 season in Greece, 04 October 2010 to 22 May 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(44):pii=2004

- Robert Oseasohn, M.D., Lester Adelson, M.D., and Masaro Kaji, M.D.Clinicopathologic Study of Thirty-Three Fatal Cases of Asian Influenza. N Engl J Med 1959; 260:509-518

- Akihisa Okumura, MD, PhD; Satoshi Nakagawa, MD, PhD; et al; Deaths Associated With Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Among Children, Japan, 2009-2010 Emerging Infectious Diseases Vol. 17, No. 11, November 2011

- Cox CM, Blanton L, Dhara R, Brammer L, Finelli L. 2009 Pandemic influenza A (H1N1) deaths among children—United States, 2009–2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52 Suppl 1:S69–74. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq011

- Sachedina N, Donaldson LJ. Paediatric mortality related to pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: an observational population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:1846–52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61195-6

- Niranjan Bhat, M.D., Jennifer G. Wright,et al. Influenza-Associated Deaths among Children in the United States, 2003–2004 N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2559-2567December 15, 2005

- Johnson BF, Wilson LE, Ellis J, Elliot AJ, Barclay WS, et al. (2009) Fatal Cases of Influenza A in Childhood. PLoS ONE 4(10): e7671. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007671

- Prandoni S. Sudden and fulminant deaths of healthy children in Italy during the 2010-11 and 2011-12 seasons: results of an online study. Jphres dx.doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2012.e29

- Wong K.K., Jain S., Blanton L. et al. Pediatrics:Influenza-Associated Pediatric Deaths in the United States, 2004–2012. Pediatrics 2013 doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1493